On May 28th, 2022, the city of Huesca was dressed up to host the Armed Forces Day military Parade for the first time. The King and Queen of Spain presided over 3,200 soldiers parading through the city. The mayor of Huesca, Luis Felipe, had issued an notice encouraging inhabitants to place the Spanish flag in windows and balconies. A few days earlier, he also issued an ordinance prohibiting the agricultural application of slurry and manure within two kilometers of the last dwelling in the city between May 23 and 29, 2022. The objective was to avoid possible negative impressions on visitors to the city.

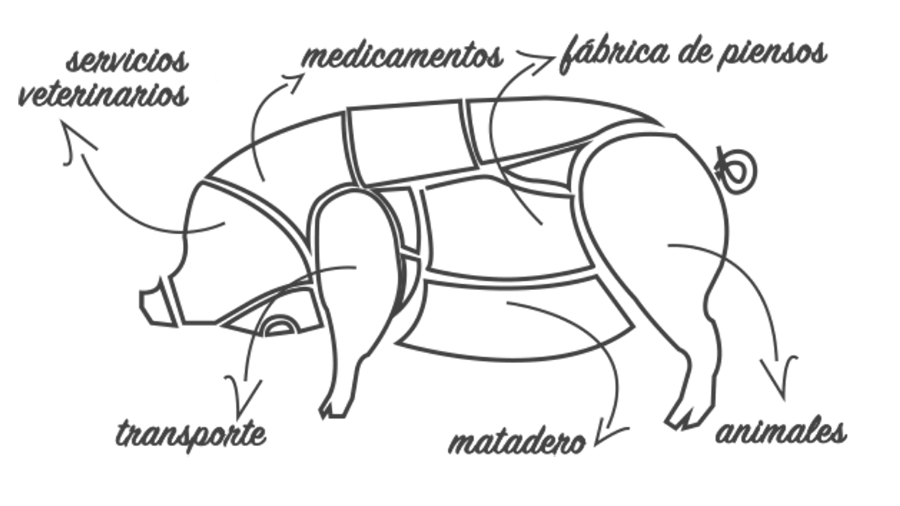

The smell of slurry is a negative impact that is immediately evident when visiting land near a pig farm. In Aragon, everyone is related to the pig industry in one way or the other, which means that resistance or critique is minimal and people who have a critical opinion of the system usually speak on condition of anonymity for fear of their neighbors and work relations.

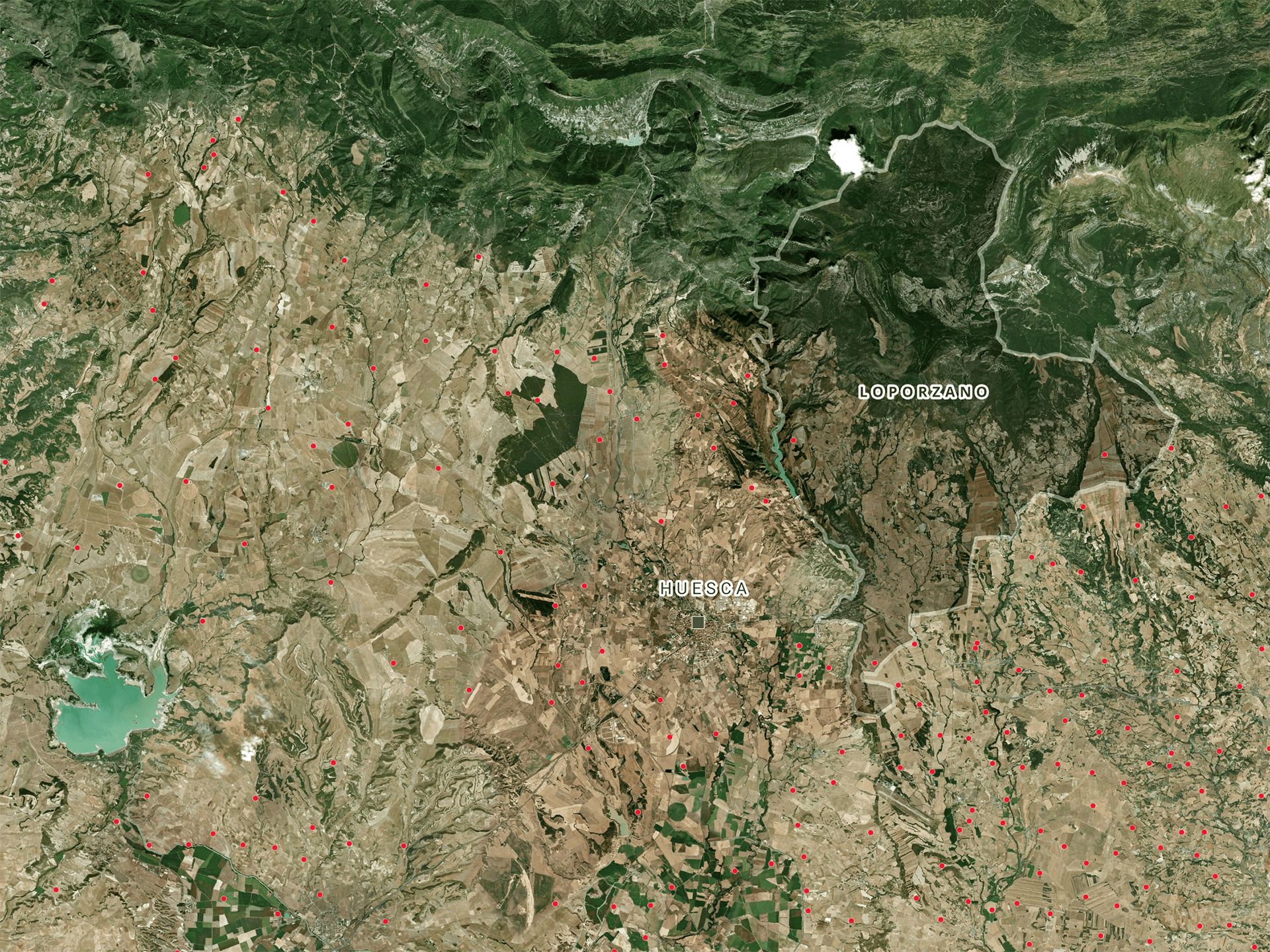

The municipality of Loporzano (in the Huesca province) is 8 minutes away by car from the city of Huesca. It sits on the foothills of the Sierra de Guara and a part of it lies within a Natural Park. From its 574 inhabitants, "half of the village is officially registered as employed in the agricultural and livestock sector", explains in an interview José Luis Bail, mayor of Loporzano since 2020. In Loporzano people are against the industrial model of livestock farming.

On Christmas Day 2015, a group of locals learned that two macro-farms were in planning at a nearby site. They organized and created a neighborhood platform to try to stop these projects. "We knew that they were going to have a very serious impact on the territory where we live," explains María José Pueyo, spokeswoman for the Platform Loporzano Sin Ganadería Intensiva (Loporzano Without Intensive Livestock) in an interview.

Pueyo states: "We are not against cattle farmers. The livestock sector is important in Aragón. Very important. It is traditional in our autonomous community. We support it, but things have to be done differently. We cannot allow the industrial pig industry not to take care of the by-products it generates, not to deal with them properly and, as a consequence of not doing things right, creating a major environmental problem".

The autonomous legislation of Aragón has expressly left a large share of the decision making around intensive farm development in the hands of regions and municipalities (more local levels of State administration). The amounts of money these can receive from pig farming exceed by far their accustomed annual budgets. Urban development planning instruments and their subsidiary norms have fostered the increase of licenses and concessions for these farms, because the autonomous regulation considers any land not classified for urban development as "land suitable for the development of livestock activity”. Municipalities can be more restrictive if they wish, but this is seldom the case.

Jorge Luis Bail, mayor of Loporzano, explains how they have managed to stop plans for several new intensive farming projects – at least for the time being – by using whatever margin current regulations allow for. "Town councils have three mechanisms to control that industry through norms. One is urban planning, ordering a certain distance to towns and scattered dwellings". The municipality of Loporzano, had been 15 years without a General Urban Planning Plan and thus held "a series of meetings for several months" to balance out the different interests within the municipality. “We managed to agree on a General Urban Planning Plan to extend the distances, to move away farms that exceeded certain maximum livestock units, to establish a certain volume of exploitation, all of which lies under our competence as a municipality".

Another measures that Bail considers can be used is "the jurisdiction of the municipalities to control slurry discharge" and the possibility of fixing periods for such discharges. However, this is not realistic to enforce "without allocating resources so that the controls and inspections can be carried out. Municipalities with an own police force can do it. We, as a small municipality, have only two bailiffs", which makes the necessary level of control impossible.

Usually, however, municipal power is not used to impose greater restrictions on the expansion of intensive farms, but the opposite. Tauste, one of the two localities with the most intensive pig farms, is an example of this. When land prices around orchards exploded due to the increased land demand, the City Council opened up the possibility of privatizing communal land. Parcels were granted to those who wanted to establish new intensive farms, recalls on interview a farmer and former municipal council member who also recounts the social pressure he suffered for being the only one in the council opposing the proliferation of ever larger intensive farms and the privatization of communal land for this purpose.

Privatization of communal land in Aragón is a historical issue which the current president of the autonomous region, former mayor of Ejea and born in the municipality, Javier Lambán, researched for his doctoral thesis. The thesis recalls how municipalities in Aragon tried to protect communal land from privatization during the Second Republic and suffered the repression of Franco's regime. With the arrival of democracy, the autonomous region pioneered the approval of a Land Bank Law to oppose the "project to expropriate thousands of communal hectares in Ejea de los Caballeros, Tauste and Pradilla". The law allowed concessions for use of the land but not its privatization or the construction of buildings on it. It did not last long and was sparsely applied. The political parties PAR (Partido Aragonés) and Alianza Popular, repealed the law after winning the 1987 elections, as they had promised in their campaigns, and replaced it with a law that did allow transferring ownership of communal land to individuals (Ley del Patrimonio Agrario). Tauste, governed by the PP, opted for this privatizing option. Ejea, however, has maintained the principles of the Land Bank Law in its ordinances on communal land. It is possible to cede the use but not to build or privatize.

A regional bill is currently being worked on, which aims to limit the development of macro-farms according to "the potential capacity of the surrounding agricultural land to receive manure". The aim is to limit "the maximum capacity of intensive livestock farms to 720 livestock units", which in practice would mean to eliminate the additional 20% that under current regulations the autonomous communities can approve, and to demand a "verification of whether the fertilizer reception capacity of agricultural lands within a 5 kilometer radius is sufficient to absorb the nutrients generated both by the requesting farm and by all authorized livestock farms within the area, regardless of the destination or management of manure of each of the livestock farms". These limitations will only affect new farm developments or extensions of existing ones.

Next chapter: How a Tesco chicken deal may have helped pollute one of the UK’s favourite rivers ››