The Campo de Cartagena is a gigantic irrigation machine operated by farmers, cooperatives and increasingly by large companies, foreign-owned multinationals or directly by large supermarkets, which farm their own land or lease from smaller landowners.

It is a sector that has been strengthened for a century by its export capacity, which was forced to convert traditional terraces to irrigation and that has managed to make southeast Spain the orchard of Europe, with a profit margin of more than 900 million euros in the Segura Basin and over 100,000 direct jobs associated. Their ability to exert pressure is strongly linked to these figures.

At the beginning of each season, rigid supply contracts are agreed to ensure that oak, iceberg or broccoli lettuce are on the shelves of supermarkets every morning of every weekday of the year in Peñíscola, San Fernando de Henares or Portsmouth.

When it comes to large groups, they control the entire chain, from the provision of seeds, the fruit and vegetable production itself, to packaging and marketing, in a scheme similar to macro pig farms.

There is also a recurring feature: many are heavily in debt. They acquired debt to grow, buy more land, machinery. They thus need guaranteed water to fulfil their supply contracts and meet their payments.

In order for farms to gain in size, land leasing has also become more common. The last agrarian census published (INE, 2009) indicates that 12% of agricultural exploitations in the municipalities of the Campo de Cartagena were rented out from their owners. All sources consulted point to an intensification of this formula in recent years, revived for example southwards of the Campo de Cartagena on land that was originally destined to real estate developments and that, after the bursting of the financial bubble, were converted to irrigated agriculture.

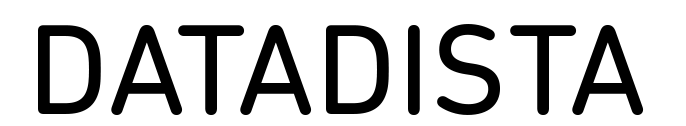

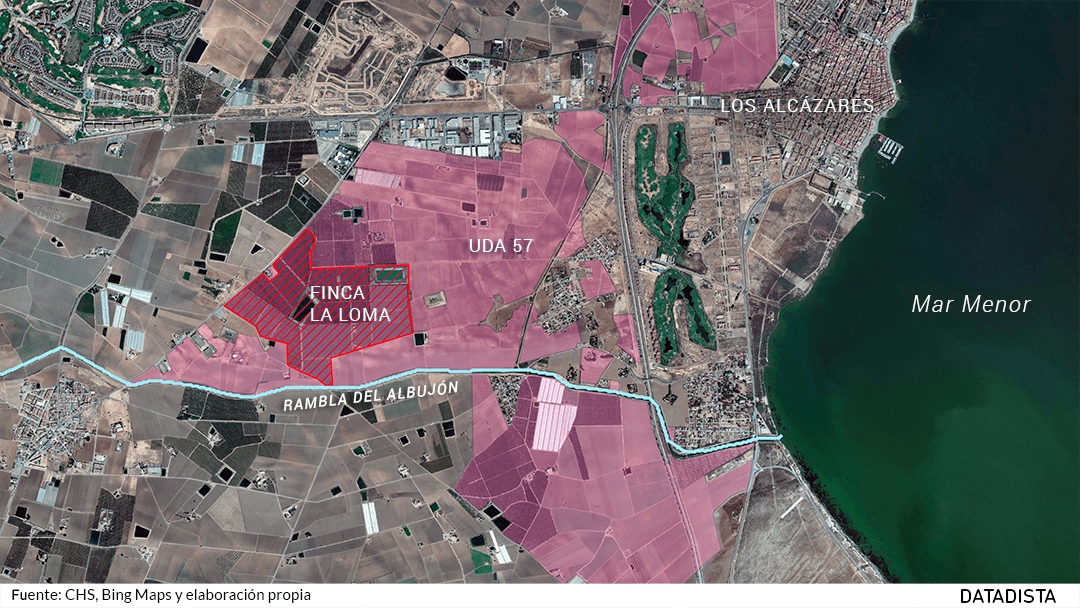

Proof of the change in the type of exploitation is seen from the sky, in the satellite images of the last 35 years collected in two reports by the Office of Environment and Socioeconomic Development of the Government of the Region of Murcia. These were provided at the request of the Public Prosecutor's Office during the judicial process that resulted from the 2015 floods in the Mar de Cristal-La Loma residential development and the Camping Site Villas Caravaning La Manga, presumably caused by changes in the topography made by intensive irrigation projects starting in 2011.

These reports, to which DATADISTA has had access, state that in the last three decades there has been a global process aimed at "intensifying cultivation, increasing irrigation, homogenising space and installing new infrastructures" on land in this case located to the south of the Mar Menor. It has not been a linear process. There are two key moments: 1997, when rainfed agriculture is replaced by irrigation, parcel sizes are modified, partly eliminating terrace structures that retained water and enclosures become larger and more uniform; and 2011, when farm units become even larger and the remains of the terraces are completely removed, ploughing is done downslope and areas on which forest was previously growing are farmed.

Where water from the transfer has been allocated, it is used for irrigation if it arrives. When it does not arrive, groundwater is the main source. In those Units of Agrarian Demand (perimeters defined by the CHS where water use occurs, but under an unrecognized legal status) where no Transfer water is allocated, groundwater has been the main source until it is possible to formalize a license to operate a seawater desalination plant. Irrigation happens no matter what. However, it is as important to have enough water in the desalination plant as it is to quickly get rid of what is left, which is why ploughing is done downslope despite the fact that this is forbidden by the Decree Law of Urgent Measures to ensure environmental sustainability in the region of the Mar Menor.

The only water that is actually annoying, paradoxical as it may seem, is rainwater. Its unpredictability is incompatible with the clock precision of this fruit and vegetable factory.

“What we need are guarantees, we need reliability, we need to know in advance what volume of water we are going to have. (...) When a farmer or a farmers' cooperative signs a commodity supply agreement with Mercadona or any national or international food chain, these are professional contracts, with penal clauses that must be complied with. Because if you fail a customer, tomorrow they will look for another supplier."

Manuel Martínez, President of the Campo de Cartagena Association of Irrigators.

Individual farmers and also large firms are investigated in the complaint filed by the Public Prosecutor's Office. This complaint gave way to the so-called 'Topillo case' for alleged environmental crimes. The practice of extracting water from polluted aquifers, desalination and discharge of flows with nitrate concentrations is claimed to have contributed to the arrival of nitrates and eutrophication in the Mar Menor lagoon, which was already under heavy pressure due to intensive urban development. According to estimates found in the complaint and based on Seprona inspection reports, four companies dumped the equivalent of 1,407 Olympic nitrate-loaded brine pools into the Mar Menor between 2012 and 2016..

BRINE AND NITRATE

DISCHARGES

1407

pools

GS Spain and GS Holding España, Inagrup, Ciky Oro and Vanda Agropecuaria (the latter while being managed by the State) allegedly extracted 11,750,649 m3 of groundwater between 2012 and 2016, treated it in desalination plants and produced an estimated 3,518,462 m3 of nitrate and brine discharge..

Behind their water needs, on the one hand, there is a turnover of hundreds of millions of euros in one of the most profitable farm regions. According to a PwC report prepared for the Central Union of Irrigators of the Tagus-Segura Aqueduct (SCRATS), the profitability per cubic meter of water in this area is much higher than the Spanish average (0.55€/m3 as opposed to 0.29€/m3 on average). The area’s fertility has also been the argument used by politicians for a century to promote irrigation. A dream confirmed by reality: irrigation is exported.

The export miracle

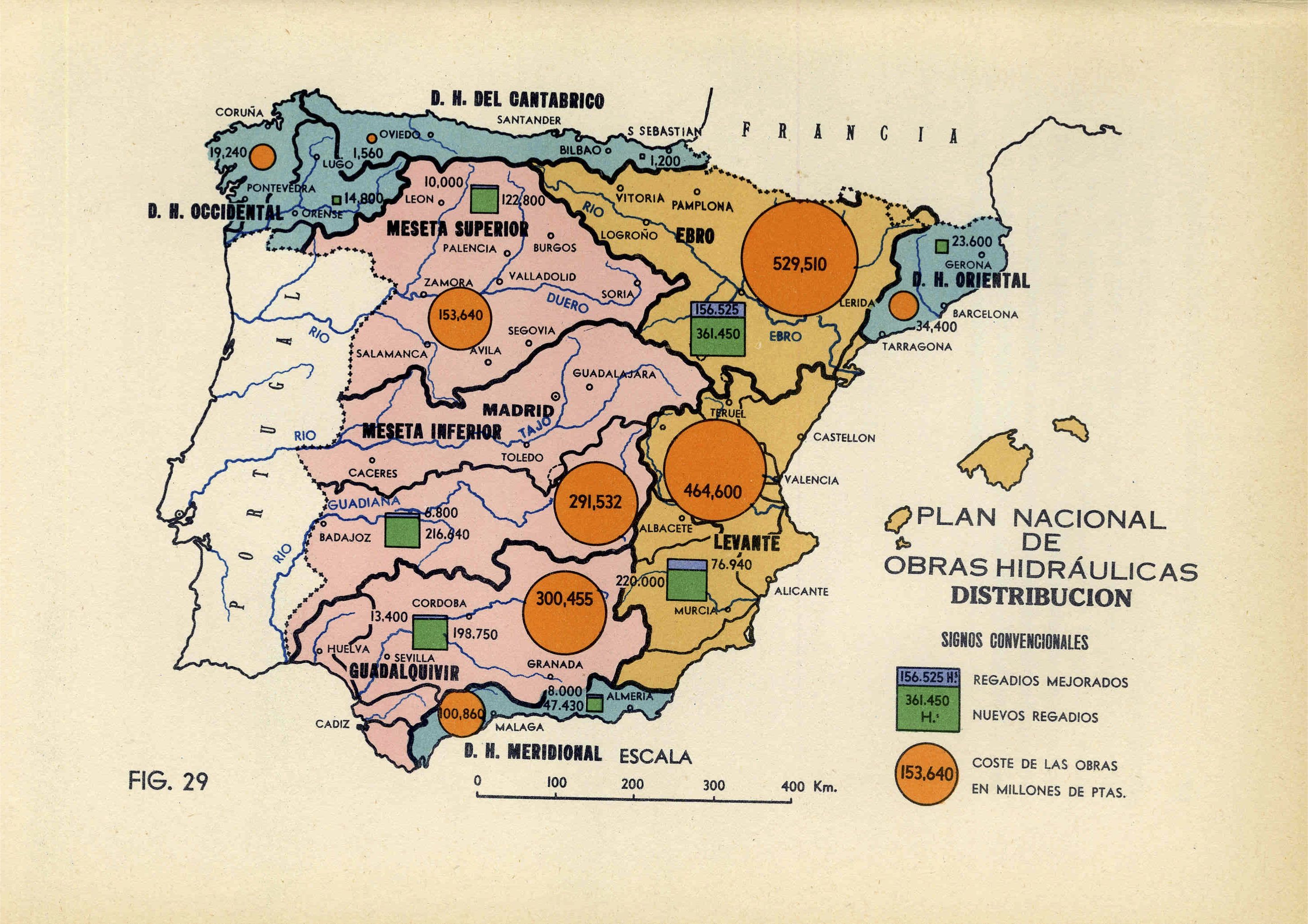

Spanish irrigation is exported and that has made it untouchable for decades. The arguments to defend it have been in force for a century and have been reinforcing economic crisis after economic crisis. The sector was a currency vacuum cleaner for decades, a relevant factor in a country with the trade balance shattered by foreign energy dependence, and one of the anchors that best resists when countries close and world trade falls. It was in the thirties of the last century, during the crisis after the crash of 29, to the point of justifying a National Plan of Hydraulic Works to bring water where it was necessary in order to enhance irrigation.

It has been in the last crisis. When exports of the economy as a whole contracted 15.5% in 2009, those of the agri-food sector made a slight 0.3%. Since then they have not stopped growing, reaching 79.4% in 2017 above the 2008 export figure. Spain exported 50,039 million euros in agrifood products in 2017 and imported 37,978 million, which represented a positive balance of 12,060 million. Agrifood accounted for 18.1% of foreign sales of the total Spanish economy. Fruits are the group with the highest positive balance (exports minus imports), reaching a positive difference of 5,525 million. The vegetables had a positive balance of 4,795 million. Citrus fruits represent the third product that receives the most income from exports of the agri-food sector, only behind olive oil and pig meat.

The large-scale fruit and vegetable export scheme dates back to the middle of the last century, although among the most significant recent changes is precisely the selling off of some of the largest Spanish-owned into the hands of foreign capital, or that British or French multinationals have chosen to establish themselves in this area. A large-scale example is Pascual Hermanos, today integrated into the British G'S group.

In the mid 20th century, José María Pascual, an Alicante-born young man of twenty years, decided to take his father's orange business further, travelling around Europe to offer his product. In 1973, the company Pascual Hermanos was born. José María offered an innovation that turned out to be a success: the sale of one kilo oranges in a mesh.

It wasn't the only innovation. His brother Antonio brought iceberg lettuce from California in the mid- 1980s and began producing it in Torre Pacheco (Murcia). In the 1980s, Pascual Hermanos occupied the first positions in the Spanish exporting companies ranking and had forty subsidiaries throughout Europe. But they lost control of the giant they had created.

Turn it for a better view

Turn it for a better viewTheir entry into the Stock market, debt and the entry of one of its competitors, Chiquita Brands, into the company’s capital, caused the beginning of the decline. In 1995, Pascual Hermanos suspended payments. In 2002, after cleaning up the group, Dole Food sold it to the British company G'S. The Pascual brothers' formula of participating in the whole process, from planting to packaging and marketing became more and more systematic.

Nowadays, mobile platforms harvest the lettuces and pack them on site. They are then taken to a warehouse, cooled and sent directly to supermarkets. Spain-grown Broccoli from January to December, advertises the corporation’s website. Oak lettuce buds all year round, it adds.

Pascual Hermanos, today G'S España Holding, created another mesh: a network of companies, each one of which fulfils a specific function.

G'S España Holdings, formerly Pascual Hermanos S.A., is the main owner of the land and rents it, along with industrial warehouses, to the group's companies that specialize in production.

The rest of the group's producing companies (e.g. Hortalizas de Europa, Frutas y Hortalizas del Sureste or Cítricos de Almenara, all of which stemmed from the Pascual Hermanos Group) sell their entire production to Sociedad Agraria de Transformación SAT, number 9909 Las Primicias, also owned by G'S España Holding. SAT in turn sells 71% of the production to Pascual Marketing, also part of the group, but working on commercialization. 18.5% is directly sold to the British parent company. Semilleros Las Primicias, the group's seed supplier, also belongs to SAT. More than 1,500 jobs depend on G'S Spanish companies, more than 1,000 of which are agricultural labourers..

Accounting records from the British parent company, G'S Group Holdings Limited, are clear proof of what its investment in southeast Spain has meant for the group and how the possibility of continuous growth based on large investments to acquire new land in 2016 has translated into income. As luck would have it, that was precisely the year when the lagoon turned green.

From a turnover of less than £100 million at the turn of the century, the British G'S group has grown to over £400 million in recent years. Profitability has also strongly grown, especially since 2010, when profits skyrocketed and "the biggest growth was in Spain" thanks to "non-stop harvest from November to May," as explained by the British records. That year, 61% of the group's income came from continental Europe, mainly from Spain.

G'S has direct supply contracts with main supermarket chains in the United Kingdom, where 75% of its sales are produced, and others in the rest of Europe.

According to the Public Prosecutor's complaint, G'S España and GS España Holding had two desalination plants, one with 1,900 m³ capacity and the other with 1,000 m³. They desalinated water from wells and sent the untreated rejection to the brine conduct, which ended in Albujón creek. They farmed 436 ha, with an estimated annual water requirement of 5,500 m³ per hectare. The untreated wastewater they produced is estimated to be the equivalent of 316 Olympic swimming pools..

Another example is Ciky Oro S.L., owned by the Frenchman Gilbert Champie, known for owning racehorses and the French agricultural company Scea de Benac, founded in 2001 to produce and sell melons. With a turnover of 20 million euros in 2017 and land holdings worth 26 million, it allegedly had three active illegal desalination plants in La Capellanía, El Carmolí and Finca El Molino, treating 540, 1,200 and 1,000 m3 per day respectively. Between 2012 and 2016 it farmed between 250 and 500 ha of irrigated land. Its estimated brine and nitrate discharge is equivalent to 555 Olympic swimming pools that went to the Miedo creek and from there, without treatment, to the Mar Menor.

DATADISTA has contacted G'S and Ciky Oro and mailed a questionnaire, as required by both companies. At the time of publication of this report, no response to the questions submitted had been received.

Regarding the complaint on the floods in the Mar de Cristal development, located to the south of the Mar Menor, whose preliminary processes are being carried out by a court in Cartagena, the prosecutor's brief includes not only the downslope ploughing and the disappearance of the terraces as alleged causes of fertilizer nitrate-loaded runoff into the Mar Menor. Companies operating in the area "agreed to carry out a series of works consisting primarily of three channels built by the owners of the plots (...) one flows directly into the Mar Menor, next to the bathing area"; another, "deeper than the first and with a wider bed, collects rainwater that falls on cropland (...) channelling it to an open area on the Loma del Castillico beach" and finally, a third that runs parallel to the RM-12 highway and has "its exit directly towards Ingres street, in the Mar de Cristal" development, next to the houses.

"When there is rain, water carrying all kinds of substances and products used in agriculture, as well as mud, etcetera, end up in the Mar Menor. This has produced some serious polluting effects by dragging fertilizers, pesticides, fertilizers and manure... and continues to do so".

This uncontrolled dumping of nitrate-loaded brine in the Campo de Cartagena is not exclusive to private companies or to the rest of farmers included in both complaints from the Public Prosecutor's Office. It even took place while one of the farms was under the State management. .

In 1997, a businessman from Cartagena who held a high political appointment at the Marbella City Council contacted an old friend, who was from Cartagena like him and whom he had known for twenty-five years. He wanted help in locating rustic estates in the Cartagena, Torre Pacheco and Los Alcázares areas, where he could establish citrus farms.

Once the operation was completed and registered under the name Inmuebles Urbanos Vanda, later renamed Vanda Agropecuaria, the farms were grouped under the name Explotación Agrícola La Loma. The Cartagena businessman ordered the construction of a 1,219 m2 house including ten bedrooms, a wine cellar, three kitchens, a chapel, a castle-style turret and a porch overlooking the swimming pool from which he conducted his business in the region.

Water was sought for in the usual place: under the ground. Wells were drilled, a reservoir was built and, as the water was highly saline, two desalination plants were installed to make it suitable for irrigation.

On March 29th, 2006, La Loma was inspected by order of a Málaga-based judge. The owner of the estate, Juan Antonio Roca, was the mastermind of an urban mafia, settled for the last 15 years in Marbella. Its numerous properties, estates, carriage collections, livestock and works of art were requisitioned by the State.

The estate, with its wells, its desalination plants and its discharges, were also requisitioned. Its administration, together with the rest of Roca's assets, was entrusted to the Malaga lawyer’s office Idea Asesores, which was also to be in charge of organising the auction of Roca's assets. La Loma was the most valuable property of were to be sold to compensate the State for the crimes commited by the former urbanism managing director. It was valued at 27.5 million euros. The website on which Roca's assets were displayed advertised La Loma's reservoirs, wells and desalination plants as part of its attractions.

On March 1st, 2017, eleven years after the State Security Forces and Corps had inspected La Loma, they returned. This time it was the Nature Protection Service of the Civil Guard, known as Seprona.

A year earlier, the Mar Menor had turned green, revealing what had been feared for decades: the lagoon, legally protected by numerous international figures, had become eutrophic. Fertilizer nitrate discharge had fed phytoplankton, which had quickly reproduced and blocked light from passing through to the bottom, in turn killing much of the seagrass.

Despite the order to stop all discharges, the desalination plants in La Loma were still working; water was still being collected from the wells and the outflow of the desalination was being discharged into a brine pipe, ending up in Albujón creek and going on from there to the Mar Menor.

Between 2012 and 2016, as the farm was under State management, La Loma had dumped the equivalent of 246 Olympic swimming pools of nitrate-loaded brine, as estimated in prosecutor José Luis Díaz Manzanera’s complaint.

In November 2017, La Loma, together with other properties grouped within the same package, was bought by Melones El Abuelo (Productores y Comercializadores de Melón S.L.) for 18.5 million euros, far from the 27.5 million that appear on the website advertising the auction of Roca's goods and also far from the 24 million that another buyer was ready to pay. The Court was informed that the latter had withdrawn the offer because of the water problems in the region.

La Loma is the straw that broke the camel’s back, if one considers that the alleged damage to the Mar Menor occurred while the Estate was managed by the Spanish State. But it is only one example of the lack of control over the groundwater in the Campo de Cartagena. Consulted by DATADISTA, the current owner, Melones El Abuelo, answers by email that they sealed the desalination plants before a Notary Public after acquiring La Loma, because they had not been sealed. They add that the wells are "documented, proofed and useful" and therefore have not been closed.

‹‹ The great botch | Who pays for the damage caused? ››